“For them, the song of the power shovel came near being an elegy. The high priests of progress knew nothing of cranes, and cared less. What is a species more or less among engineers? What good is an undrained marsh anyhow?”

Aldo Leopold-A San County Almac

Without the beaver, there would be no Detroit as we know it today. The French settled this area as a fur trading post. But, this has always been beaver country. The Indigenous Anishnaabe people called them amik, long before the French arrived. Detroit today, is better known as the motor city. These two things, European settlement and industry, led to the absence of the beaver here for an estimated 150 years.

These histories collided again, when the beaver returned to the Detroit River in 2008. They were first spotted on the grounds of the Conners Creek Power Plant. It was the perfect unintentional wildlife refuge: 66 acres, fenced in, multiple access points to the river, and very little human activity. Conners Creek was so close to Belle Isle, a 982 acre island park situated in the Detroit River, it makes sense the beavers would set up there soon after. Beaver can now once again be found on the entire length of the river. They have even been spotted on Detroit’s other river, the Rouge, including at its most industrial point, Zug Island. It’s worth noting that In 2019, the Conners Creek power plant was demolished and the majority of the land will be used for a new FCA Jeep plant.

I came to know the Detroit beavers in 2015, while I was still getting to know the birds. When I began birding, I had very little experience, knowledge or skill. Growing up, there was no creek running behind my house, I didn’t play in the woods, I’ve never even been camping. But here I was anyway, with an interest in birding. So, I started spending time at the wildest place I could think of, Belle Isle. One day, I followed a pair of Hooded Mergansers from a small lake, to the canals, and ended up on a trail I never knew existed. I started visiting it 3-4 times a week.

At this time, I was still pretty early on in my birding practice. I hadn’t yet learned about bird behavior, migration, habitat, or range. I had no idea that Belle Isle is a rare mesic flatwoods forest, or that this area is an important stop for migrating birds. But I was discovering the healing benefits of nature. I don’t have the language to verbalize exactly what birding did for me, but it felt like the world had been opened up. It allowed me to shift my attention and offered me a new way to see and connect with the world. I called birding my therapy, and I needed a lot of it. Everyday I was seeing something new. I bought a small camera and started taking photos and videos so I could research what I was seeing when I got home.

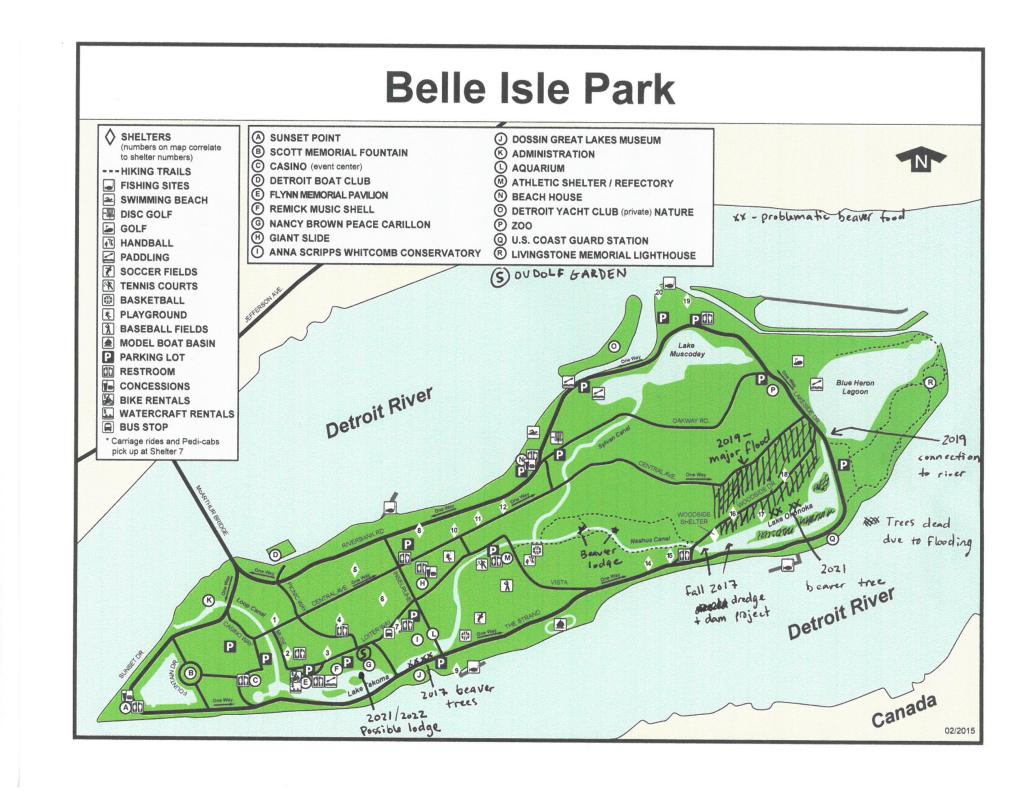

I was spending so much time outside, I inevitably started paying attention to more than birds. I started seeing evidence of the beavers on Belle Isle in the fall of 2015. I saw small trees chewed to a sharp point, and tail slides on the banks of the canal. Once the leaves fell off the trees, a lodge became visible.

I had no idea if it was active or not, but the fire was ignited and I became consumed with seeing the beavers. I started researching them, but most information I found online centered on trapping the animal. I eventually found a blog by Bob Arnebeck, who seemed to find great joy in watching beavers. He shared a lot of helpful tracking information. After researching and searching for months, I decided to reach out to Bob to ask for his help. He had spent a few years in Detroit and was familiar with the area. He patiently and expertly answered all my questions. His work was invaluable to my development as a naturalist. I learned about the differences between lodges and dams, what a winter cache was, how to tell if a lodge is active, the best time of day and year to look for them. He encouraged me to be patient, it had taken him a year to first see a beaver. Then in March 2016, I finally observed the beaver for the first time!

I was in absolute awe. It’s size was unbelievable, it’s tail unmistakeable. It seemed to be floating on the surface of the water, moving so natural there you could barely see a ripple. At some points, only it’s face and ears were visible, reminding me of a hippo, and it might as well have been one to me. I’m from Detroit, a city perhaps just as famous for its deindustrialization as its industry. This beaver was the wildest animal I had ever seen outside of a zoo. I had been searching for months, and here I was finally witnessing it. I could sense that they are peaceful animals, and I felt at peace watching them.

By Spring 2016 I had been observing them regularly. I was learning their routes and patterns. One morning, I was watching them from the footbridge over the canal, when a woman with binoculars came walking up the trail. I knew the sound of her steps could scare them, so I walked toward her and gestured for her to keep quiet. She whispered “what do you see?” I told her beaver, and she said very confidently “there are no beavers in Detroit.” We tiptoed back to the bridge, and there he was, floating in the water with his unmistakable tail in full view. Her jaw dropped. We stood there, in complete silence, taking it all in. When the beaver left, she turned to me, shock still on her face, and thanked me for sharing it with her.

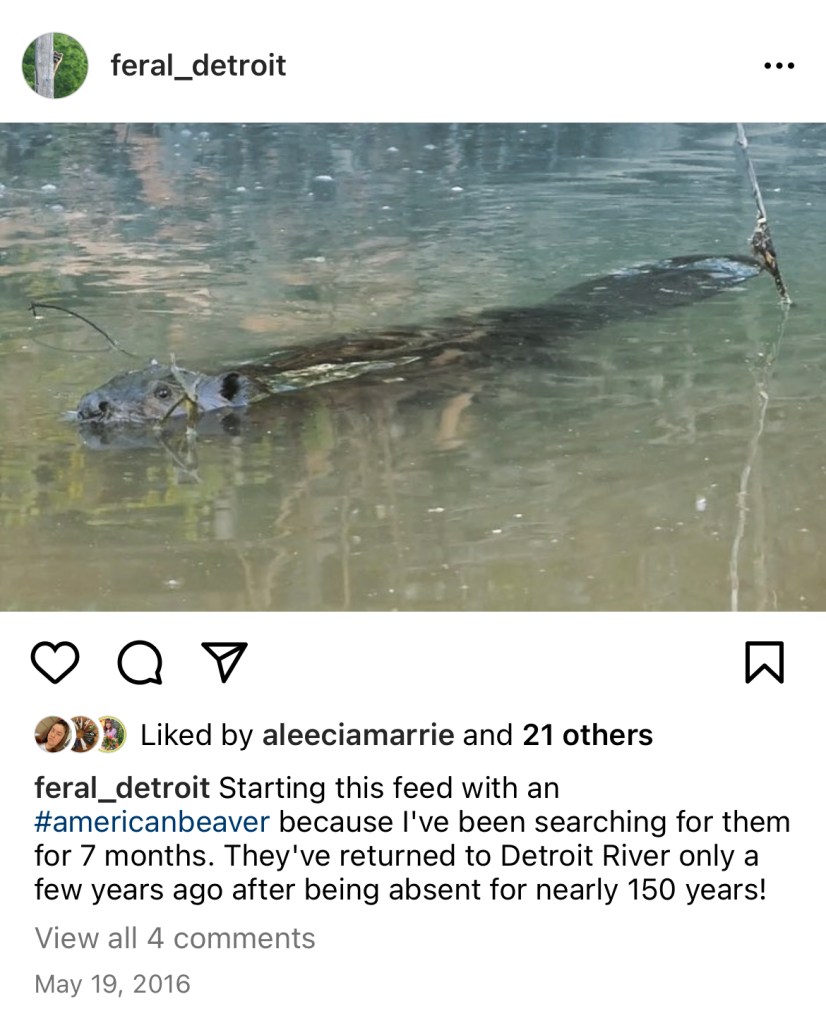

This is one of the encounters that inspired me to start sharing my sightings. The more I witnessed, the more shocked I became that so much life has been existing alongside me, and I never paid attention to it. It seemed to me, that many other people lacked this knowledge too, and I felt called to bring attention to the birds, the beavers, the plants, the bugs. Mary Oliver once said “attention is the beginning of devotion.” That is what I was hoping for. So, I started the instagram page @feral_detroit a few days later in May 2016. My first post was the beaver.

By spring 2017, I’m consistently observing, learning, photographing, posting, teaching. The seasons kept changing and I kept doing what I do. My new “nature as therapy” philosophy was tested, but nature kept providing me with what I needed. I saw a coyote on the beaver lodge, and posted the photo to instagram. A local journalist asked to run the photo in the newspaper.

I observe the beavers many times that spring and summer, and get a chance to really observe their behavior.

Fall 2017 is a turning point in the beaver/human relationship on the island. The Michigan DNR started a large “habitat restoration” project on an inland lake, Lake Okonoka. They have plans to improve fish habitat, and will begin dredging the lake. They cut the canals off from the lake for the project.

The beaver’s lodge was located in the canal, and they fed on small trees and vegetation along the trail, and also in Lake Okanoka. Now, cut off from the lake, and needing to eat, they must travel west through the canals, to the more developed part of the island. So the hungry beavers take two small Willow trees in front of the Conservatory, a main attraction on Belle Isle.

Nothing exists in a vacuum right? Detroit is rapidly gentrifying, and like the city, the park is changing. Belle Isle is getting busier, and it’s getting whiter. So now, we’ve got park users who are unhappy with beavers for eating trees, as if the trees do not belong to them. The DNR takes notice, and there is talk of removing the beavers to save the “important ornamental trees.”

The local paper runs a story about it, and contacts me for a photo of the beaver. They also ask my opinion on their possible removal. To me, there was no beaver problem. There was no imbalance between beaver and trees, the willows belonged to them. This was all a matter of cosmetics. The head of the park acknowledges in the article that the beavers had been cut off from the lake due to their construction. The remaining willow trees in that area were wrapped in beaver proof fencing and the beaver kept traveling to find food. They even taste tested the bridge to see if it was edible.

So the seasons keep changing. I keep doing what I do. The DNR keeps getting grants, and keeps making its “improvements.” I am only seeing the beavers sporadically now, I’m no longer able to track their movements. The beavers are still here, but we are on different paths.

In 2019, state completed another large project on Lake Okonoka, connecting it to the Detroit River. Coincident or not, the forest starts to flood and the trail is now inaccessible in the spring and summer.

The constant construction and never ending roster of events starts getting to me. I start feeling frustrated and stressed when I go to Belle Isle, and I can’t find the peace I once felt here. I starts felling like extension of the gentrification in my neighborhood. I start spending more time birding other places in the city to escape it. Cemeteries and railroad tracks become some of my favorite places.

In 2020, I am outside almost daily and find myself back at Belle Isle. The island is facing more historic flooding, and again I cannot access the canal trails. Most of the roads are flooded now too, and a large portion of the island is inaccessible. I see the beavers sporadically, in Lake Okonoka once or twice. And now for the first time I see them regularly in Lake Tacoma, on the more developed west side of the island, near the trees they ate in 2017. I am happy to see them, like seeing an old friend.

But I’m also worried, because of a new development here, a new multimillion dollar garden.

Like so many, I spend the fall and winter of 2020 to 2021 just trying to stay afloat. On a very cold sunny day in February in 2021 I am able to finally get outside again. I see a beaver on Belle Isle for maybe the last time. It’s just as memorable as my first encounter. I was walking along the canal trail, now frozen. One of the things I like to do in winter is find water, and see what birds come to drink.

On this day, I found a hole in the ice and watched as Cardinals and White-throated Sparrows visited for a drink. I saw the water move, but I didn’t feel a breeze, and it wasn’t windy. I crouched down thinking something would pop out of the water, a mink maybe. To my surprise it was the beaver! He was so close to me he reacted to the sound of my camera shutter, we both paused. I am not sure I’ve ever been this close. I feel the peace like the first time I saw him. It feels like maybe we are the only two outside today, and I find solace in that. He starts trying to lift himself out of the water and onto the ice.

Once he finally lifts himself up, he takes a drink of water, and starts walking toward the woods. I give him the space he needs, and we go our separate ways.

In spring 2021, the DNR begins work to restore the Mesic Flatwoods. Another multi million dollar project. More major construction, this time all over the Nashua canal trail. One of the bridges I’d often watch the beavers from was removed. Roads are unearthed, removed, and left in piles on the side of the trail. By spring 2021 Belle Isle feels like a place I don’t know anymore, and I rarely go. I walk the lighthouse trail more often than Nashua Canal. Come fall, I notice the beavers have taken some Aspen Trees off a small island in Lake Tacoma, near the new garden. I suspect they’re building a new lodge. I also notice two large, old, willows that they’ve chewed on the east end of the island, in Lake Okonoka. I know this will be an issue and I make a video to document it. These are the largest trees I’ve ever seen them take or chew on the island. Still, there is no dam on Belle Isle, only lodges.

In February 2022, the DNR unceremoniously traps and kills the Belle Isle Beavers. A journalist from the Metrotimes calls me to ask for photos to use in the story. He also asks my opinion on the DNR killing the beaver. I start almost every interview, meetup, and conversation these days by saying that I am just a person with a camera. I say that partially as a point of pride, I am a self taught urban naturalist from the hood, and I get to speak for the beavers. But it’s also to say that I don’t know everything, that I may get it wrong. I have the photos, I have the knowledge, I have taken the time to get to know the beavers, I have found a way to connect to nature in this place, but I do not have power or credentials.

In the article, Ron Olson, who does have the power and the credentials, speaks for the state. He is the head of parks and recreation for the Michigan DNR. Olson makes a few statements in the articles that I disagree with. He says that there were about 8 beavers on Belle Isle, and that would be my guess too. But he says “that’s a lot.” And that I do not agree with. He says that “each mated pair will have up to four offspring.” True, beaver families are typically around that size, but there is only one mating pair in the group, who mate for life. Beavers like most animals have and defend territories. I trust the beavers to decide amongst themselves how many beavers is too many. He suggests that beavers have been causing flooding on the island and that feels like a straight up lie. The beavers on Belle Isle were bank beavers, and there is no dam on Belle Isle. He says that beavers “belong in the wooded area,” and they do. But when we are constantly encroaching on “the wooded area” who gets to decide where it starts and stops? There is exactly 339 feet between the edge of the woods to the edge of the water where the beavers ate the willow trees that got them killed. I measured it myself. Perhaps the playground installed as part of a “habitat restoration” project is what doesn’t belong.

He says the beaver cull is a calculated management strategy. In a Detroit Free Press article he says that the state’s “mantra is to steward the land. With that comes prudent and proper management plans.” He goes on to say “these kinds of things, they are difficult for some folks to cope with.” And he’s not wrong, it is difficult to cope with the death of the beavers I’ve been observing for several years. But it is even more difficult to cope with the arrogance of the state. He says that live trapping the beavers would have been too traumatic for them. I guess death is somehow less traumatic to the beaver than trying to live on land stewarded by the state.

The state does not own this park by the way. In 2013, Belle Isle was leased to the state of Michigan for 30 years by an emergency manager, appointed by governor Rick Snyder, the guy you who poisoned Flint. The Detroit City Council unanimously voted against this deal, but lost. So the state gave itself the park, and the people never got a say. W are supposed to trust all their decisions?

In his book Where the Water Goes Around, Bill Wylie tells the story of a sacred tree that was cut down on Belle Isle by the state. When questioned, they responded that had they known, they could have saved it. In the essay “From Wahnabazee to Penskeland” from his book, Bill says “that’s the deal, you have to know the story, the layered meanings of a place. Sacred trees, like sacred rocks, may not speak for themselves, but their destruction can turn to curses.” Sacred too, is the beaver.

It’s insulting that Olson would suggest that we are just too sensitive, and that we just don’t understand their management plans. I have seen with my own eyes that they do not care about this land. They allow billionaires and millionaire real estate developers to sit on their advisory committee. They allow an Indycar Race here. They mow native wildflowers every year, Spring Beauty, Fawn Lily, Milkweed. They take weedwackers to a wetland. They pay millions to “improve” our trails and then drive their cars on it.

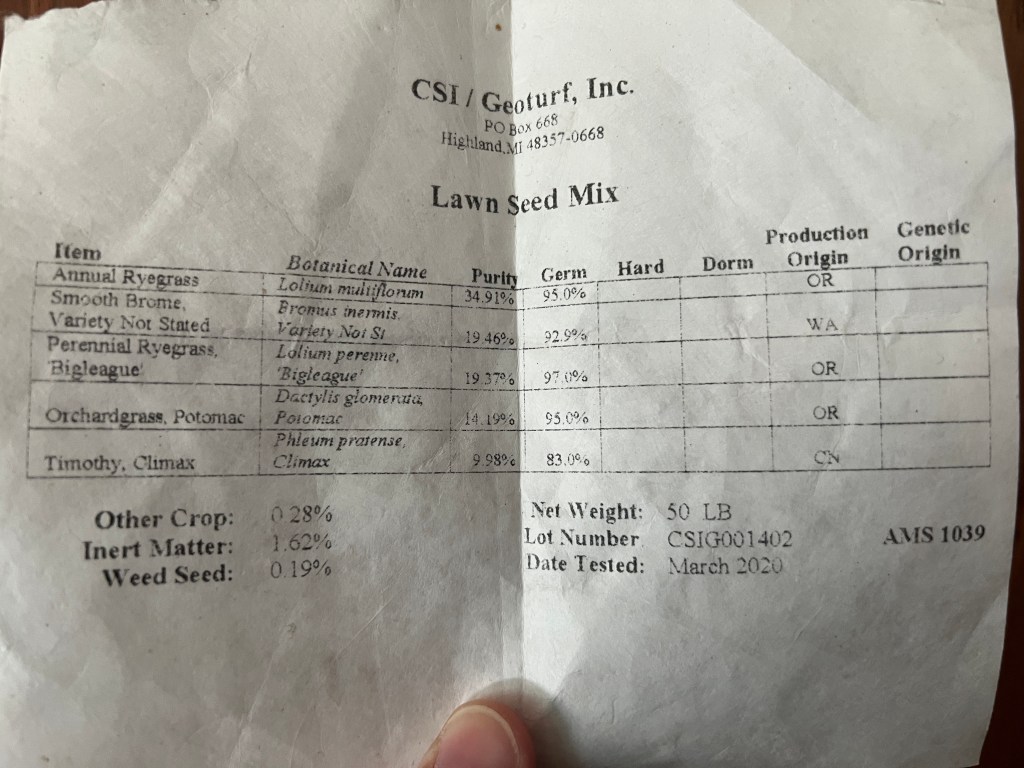

They tear out asphalt trails only to leave the asphalt sitting on the bank, while the other hand looks for money to control erosion. They repave that same trail with new asphalt two years later. They refuse to protect the first Bald Eagle and Osprey nests in a generation, because they’re not legally obligated to. They “restore” native bird habitat, by planting European grasses, against the advice of experts. They disrupted a Great Horned Owl’s Nest and an entire spring bird migration with heavy construction. They connected an inland lake to the Detroit River and flooded and kill the oak trees that makes this forest special. I could go on, but this post has to stop somewhere. The state sees this park as property, as a resource to be extracted from. They cannot fathom our love for this place.

I went to Belle Isle yesterday. The Red-winged blackbirds have returned, like clockwork. It was hard to hear their song over the machines of so called progress, but they sang anyway.

“This is a prayer to the One who flows around us, over us, in us. Come. Come in judgement and mercy. Come home like the sturgeon. Glide as a swan and strike. Slither like a snake unexpected. Reegineer this world only as the beaver. Come as wild grass that grows through the cracks. Break from below the concrete idols. Dance on its rubble at a wedding. Grow like truth at the poor one’s door. Unite as all relations. Burst forth like the buried stream. Rage like a bridge afire. Let the gatehouse crumble. Let the governor and his petty minions fail. Let the cop cars stall and the guns go silent. Let the wounds release their victims. Set the bathhouse prisoner free. Let the invasive species wither at their roots. Let the island be sown or go feral with love. May the sacred commons spread. And yes, may the waters go round. Amen.”

“Where the Water Goes Around: Beloved Detroit” by Bill Wylie-Kellerman

I share exactly the same thoughts and feelings. Thank you for speaking so eloquently and factual.

LikeLike